This is from a paper I wrote recently for a competition at WoW. The paper was thrown together over a span of three days (so don't be too hard on me) in between work and getting stuff done for my best friends' wedding. I am also having several formatting issues, so please bear with me as I edit the page. Long paper is long.

One of the biggest challenges I've encountered as a re-enactor is finding quality information on Ottoman art and artifact within the Society timeline. The Ottoman Empire spanned from the 14th Century until the 1920’s, so when researching you have to pay close attention not only to the dates, but to visual clues. After staring at pictures of textiles and miniatures for years, patterns started to emerge. This is my attempt to make sense of a visual history with regards to its textiles as it falls within our time of study.

I

feel that Middle Eastern personas have often been looked upon unfavorably

because a large portion of its participants have a lot of misinformation, resulting

in a very modern aesthetic. While my focus is on Ottoman textiles, it should be

said that a lot of the resulting research can be applied across much of the

Middle East. Most garments were not cut with busts exposed and women didn’t all

walk around naked, nor were they completely covered up. To summarize all of the cultural aspects,

sumptuary laws and clothing styles across the lands and time of the “Middle

East” would be an immense task. One of

the ways we can best make our garments more correct is to have more knowledge

of what patterns are appropriate for what we are attempting to recreate.

Sometimes the only difference between “Persian” and “Ottoman” garb are the

design elements on our fabric. In my attempt to make Ottoman garb more

researched and defined within Society, I have a few windmills: Garments have

necklines not bust lines, stripes are bad, and Paisley is not period.

Paisley

is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as, “a distinctive intricate pattern of curved feather-shaped

figures based on an Indian pine-cone design.” The modern design is named after

a town in Scotland whose textile mills were known for producing a large

quantity of woven fabrics displaying this popular textile motif in the 19th

Century. Paisley again became popular in modern fabrics in the 1970’s. It is

this modern design that we most often find in fabrics that one might choose to

represent Middle Eastern.

The

origins of Paisley may well be “period” for India, where the design element

originates, but a preliminary glance suggests that appropriate designs are

dissimilar from most modern designs available. Overall, paisley is not suitable

for use in Ottoman garb within society time period. Yet, paisley is one of the

most commonly found design elements used by recreationists when creating Middle

Eastern garb.

I

tend to have a permissive attitude about many things involving the Ottomans

because of the sheer amount of peoples and cultures incorporated into their

empire. We can draw lots of assumptions about design and fashion simply based

on the many cultures that the Ottomans conquered or bordered, and the

possibilities of trade. By the 16th Century much of Persia became

part of the empire, so it is reasonable to assume that art, literature and

fashion made a merger. When viewed hundreds of years later it is easy to make

mistakes in judgment of one culture over another.

With that in mind we have to

incorporate cultures such as Mongol, Persian, Byzantine, Greek, Seljuk, Mamlûk,

Berber, and even Rus into our pile of potential influences. During some periods,

specific types of art styles came in vogue that make it difficult to discern

whether something is Ottoman or not because the artist in question might have

been Persian, for example, and so the art style may reflect that.

This

paper is not about paisley; instead it is about what is desirable and

appropriate for the re-enactor. Extant Ottoman garments in museums tend to be

royal, ceremonial, or otherwise male. There are many paintings, travel drawings

and miniatures that show more mundane clothing, but they may be subject to

artistic interpretations. To help shed light on the designs used in Ottoman

garments, I have looked at painted miniatures, illuminated manuscripts,

textiles, Iznik pottery and tiles, and the flora of the Mediterranean. I have

tried my best to use samples of pre 17th century textiles but, much

like Elizabethan research, relevant styles cross over until the end of Osman

the Second’s reign in 1622.

Floral

and Leaf Designs

Where possible, I have tried to include a

botanical example. It is likely, however, that the species that were available

at the time are not quite the same as the examples shown. I have not included

every botanical design, only the most common.

Saz Leaves

I have listed these first

because, if any one design is guilty of misleading the casual observer into

thinking it’s paisley, it would be the Saz style leaves. This artistic style

was popularized by court painter Shah Qulu during the reign of Süleyman the

Magnificent.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/images/h2/h2_52.20.17.jpg

The vine and saz textile below also includes pomegranates.

http://home.earthlink.net/~al-qurtubiyya/Fabric/Bursa_or_Istambul_late16th.jpg

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgu8ryGdZPin_3njoOBzpHQ0-Riasn0Ap2ww9ACsaUx-nOwWoNmCrxTde6J2Iohf92u84oKHBRsV4sZUYa62MGw7inhwqprqe3ZJlhNnr05Z3hyETNlaQlQTuqtHdmFWpnSzyeRQRGgJgA/s320/kaftan+kurk+%282%29.jpg

The caftan (above) shows a network of climbing vines

and saz leaves.

Saz-style refers to a school

of art, much like we tend to refer to the “Italian Schools.” Not only is it the

shape of the leaf that is important, but often the colors or shading that makes

it so distinctively “Saz.” It is believed that the type of brush used in the

painting of saz leaves is from where its name is derived.

Cypress

The cypress is a conifer that

is prevalent throughout the Mediterranean. It is tall and thin and lends itself

well in scale to fill out the background of a leaf design. While I have found

very little evidence of its use in clothing, I felt it worthy of mention as a

design element as it is prevalent in miniatures, tiles, and other textile art.

http://media-cache-ec0.pinimg.com/236x/70/82/18/70821802d763219c3f1ea914ec660018.jpg

In this caftan it is my suspicion that the thick vines are

representative of Cyprus.

I should mention here that Iznik, much like Saz, is a term

referring to a style of pottery but, like Paisley, is also representative of a

region. Iznik pottery is called so for the art it contains, but the manner in

which it was built as well as the quality. Many of the motifs are saz-style art

done in a different medium; glazes. Tiles can be a great resource for textile

designs when looking at miniatures.

This 21 tile Iznik

wall design includes Roses, Tulips, Saz, and Irises.

http://mini-site.louvre.fr/trois-empires/img/ceramiques-ottomanes/ceramiques-ottomanes8z2.jpg

Palmet or Lotus

The use of lotus and peony

designs is evidence of Chinese and Mongol influence. They are often accompanied

by elaborate scrolls or cloud-vines. This is one of the many examples of the

difficulties in discerning a Persian piece from Ottoman works, as Persian art

is rife with very similar patterns. Often to differentiate between Persian and

Ottoman you might look for bolder prints.

http://www.ee.bilkent.edu.tr/~history/Pictures2/Yeni/costume3_2.JPG

Caftan of Bayezid II Includes several types of flowers

and saz leaves along with the palmet design

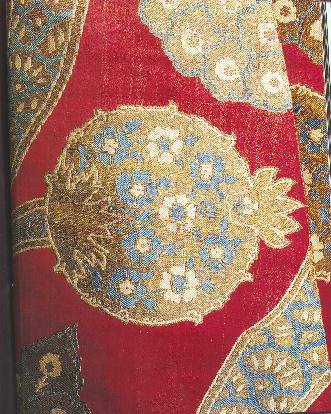

Pomegranates

Pomegranates are a symbol of

life and fertility and thusly are very prevalent in Ottoman textiles. The fruit

is common in Ottoman cuisine and literature.

http://media-cache-ec0.pinimg.com/736x/5c/a3/12/5ca312eb00699a405ef53810d9ea0673.jpg http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00044/s44t4_files/T3d.jpg

These two are pine

cone and pomegranate fabrics from caftans. Sadly, the example on the right is

post society timeline. As it was an honor robe for a sultan, I think that it

was created to resemble an earlier sultan’s robe because it is similar to a

piece I’ve seen but much bolder of a print.

Tulips

Tulips are not native to the

Ottomans, but quickly grew popular. The species of tulip represented in the

textile motifs is most likely extinct or nearly so. The Dutch tulips we are so

used to seeing are fuller but, the Ottoman tulip is wispy and has beautiful

long tendrils. The botanical picture below is the closest species I could find

to what is believed to be the Ottoman tulip.

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_PuoJ2BG8mkc/SXciJ6NiDWI/AAAAAAAAAYk/3cX2dG_ntn8/s400/acuminata.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_PuoJ2BG8mkc/SXciJ6NiDWI/AAAAAAAAAYk/3cX2dG_ntn8/s400/acuminata.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_PuoJ2BG8mkc/SXciJ6NiDWI/AAAAAAAAAYk/3cX2dG_ntn8/s400/acuminata.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_PuoJ2BG8mkc/SXciJ6NiDWI/AAAAAAAAAYk/3cX2dG_ntn8/s400/acuminata.jpg

In the 16th

Century much bolder prints start appearing in noble garments. This may be

because they were easier to see in royal parades, or because they showed

affluence (bigness), or simply for the sultans to separate their cultural art

from those whom they had conquered. The tulip is one of a few designs that when

printed boldly becomes a kind of logo for the sultanate. In contrast to many

other patterns you see throughout this paper that incorporate the tulip, the

garments below show the bold printing of them.

http://media-cache

ak0.pinimg.com/236x/a1/de/a5/a1dea57e9acfdc5ad01e52737456ed77.jpg

http://media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/db/c2/85/dbc285f568007feb0bddc88d481f5c80.jpg

Carnation

(Dianthus sp.)

This is another floral species that is dissimilar from

what we think of as the modern carnation. The key element of the species that

was most likely available in the Ottoman Empire is a smaller quantity of

defined petals with jagged edges, or straw-like, explosive petals.

Carnations are most often

used as a smaller motif within a larger floral pattern. Below are two examples

of carnations being used as a bold print. On the left a painting of a garment

with bold carnations, on the right is a cushion cover.

http://www.hotspots-e-atlas.eu/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/carnations-296x300.jpg

Hyacinth

Hyacinth flowers are worth a

mention as a filler design. It is a popular element in Iznik pottery and some

non-clothing textiles. It is not seen as a bold print and instead is often a

small part of a busy floral design.

http://www.turkishculture.org/picture_shower.php?ImageID=2147 http://mini-site.louvre.fr/trois-empires/img/ceramiques-ottomanes/ceramiques-ottomanes11z2.jpg

(Left)

17th century Pillow Covering featuring Hyacinth.

(Right)

Iznik tile with lots of hyacinth, tulips, carnations and cloud scrolls.

Rose (Damask)

The Damask Rose is made into

Rose Water and used for cleansing and welcome, as well as in cuisine. It is

also used as an oil for cosmetic purposes.

Damask roses have a more

complex petal construction than the modern European rose. Notice the feathery

shape within the rose leaf and the flanges on the bud design (right) is similar

to saz leaves.

(Left) Caftan of Selim II shows a small repeating print of

roses and vines. I was unable to find a close-up of the roses. http://www.turkishculture.org/showpic.php?src=images/image_all/Clothing/Ottoman%20Clothing%20and%20Garments/topkapi19.jpg

16th century fragment with a type of rose. http://www.wilsonartcontract.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/ottoman-textile-yellow.jpg.

Clouds and Çintemani

Clouds are another motif that

blur the lines between Persian and Ottoman, as the cloud design is something we

tend to associate with Asian culture. The Ottoman clouds are usually less

scrolling and more elongated wavy lines.

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgvKUa6Ku3LZWK4vgUEisSRrnWhf_WMynJGVe7d1BKQcJoBBVH6pzjkLxcw_Osn2j9p4khU7Hz6qRGW_jR_YxhFcxm_hJnRAa2bn157bY8neXRug7y40Y9MTzIpPINGp0tq3d2UMLVSWCI/s320/kaftan+cintemani+detay+%282%29.jpg

Here you will see crescents

which are more often than not, a version of ҫintemani. Çintemani is

typified by three circles, sometimes having eyes inside of them.

https://encrypted-tbn3.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcQYVyaXUbYsxEcUXRNRZGf_sNDE7T6HxH1HzqSomAdkwPEe6QhpVg

Several sources refer to the ҫintemani

as a symbol of protection. It is my suspicion that this is similar to the “evil

eye,” which has been an amulet of protection in Islamic lands for centuries.

As mentioned in the tulip

section about the concept of a logo, the ҫintemani motifs are definitely the

design that best illustrates it. They are bold and simple but yet very powerful

symbols.

http://home.earthlink.net/~al-tabbakhah/cintamani/Palace_Dancers.jpg

Ogee

Ogees are pointed ovals.

Often these geometric designs will have other elements such as floral, leaves,

or cintemani. Ogee designs can easily be mistaken for Persian medallions unless

you use florals or other contextual clues to separate them.

The above ogee design incorporates Tulips, Pomegranates,

Carnations and Saz.

Miscellany

While there are a great deal

of animal motifs in Iznik pottery and painted miniatures, it is seemingly rare

to find it in textiles. What I have come across is mostly avian in nature.

There is a miniature where it appears to have a repetitive swan design (right),

and there is also this peacock feather design (left):

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/images/h2/h2_52.20.15.jpg http://www.nndb.com/people/713/000113374/selim-ii.jpg

Modern Fabric Examples

I can’t condemn modern fabric choices and not give

examples of some that are acceptable. Here are some samples of fabrics that I have

found at a retail site that are accessible to the re-creationist.

Not all of these fabrics are wearable, per se, but could

still be used for covering pillows or making tents. In the selections below you

can see carnations, pomegranates, roses, palmets, saz leaves, ogees and tulips.

http://www.joann.com/images/67/80/3/xprd6780381_m.jpg

A Note about Research

The painting on the above shows women inside the palace. Not

only are the women wearing fabrics with ҫintemani and ogee but the walls and seating are covered with it as

well.

This is an example of where the ҫintemani had formed a quatrefoil which may look

like a geometric flower print from a distance. We can see in the Topkapi Palace

today that there were lots of tiles and textiles on walls and ceilings with

many overlapping patterns.

Palace of Gold and Light Museum Catalogue

Sometimes it’s hard to get decent pattern information from miniatures because the artist would spend more time patterning the background of the painting than what the people were wearing. I suspect that is in part due to the fact that the figures where some of the smallest things in the painting. But the patterning in the background can also give us clues to motifs that the participants might have been wearing (above). And sometimes we get lucky with a painting and get incredible detail on patterns (below).

http://www.info-regenten.de/regent/regent-d/pictures/turkey-Selim-II.jpg

I have tried to show not about the

origins of paisley but rather a look at what designs are more appropriate for

Ottoman garb. It’s easy to see how, at a quick glance, one would think that

paisley is a desirable design element for use in re-creation. Stripes are also absent

from pre-17th century ottoman clothing. There is still a lot of

confusion and misinformation about Middle Eastern design and clothing that is

being perpetuated by well-meaning recreationists. It is my sincere hope that, with

this and further information, those who attempt to recreate Ottoman and other

Middle Eastern garb will make wiser fabric and design choices as we go forward

into the past.

http://home.earthlink.net/~al-qurtubiyya/16/Cod.Vind-palace_women.jpg

Bibliography

“A brief

history of paisley.”

Akar, Azade. Traditional

Turkish Designs. Dover Publications, Inc. Mineola, New York 2004.

Ettinghausen, Richard. Arab Painting. Rizzoli International

Publications Inc. New York, 1977.

Evani Ceramic. “The Meaning

of Design.”http://evaniceramic.com/the_meaning_of_design.php

Hali.com “Flora Islamica:

Plant Motifs in the Art of Islam in Copenhagen.” http://www.hali.com/news/flora-islamica-plant-motifs-in-the-art-of-islam-in-copenhagen/.

Ibrahimoglu, Bikem. “Caftans

– Ottoman Imperial Robes.”

http://bikemibrahimoglu.blogspot.com/2010/04/caftans-ottoman-imperial-robes_22.html. April 22,

2010.

“Introduction to the Court Carpets of the Ottoman, Safavid,

and Mughal Empires” http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/court-carpets-of-the-ottoman-safavid-and-mughal-empires-an-introduction.html.

Kazmi, Nuzhat. Islamic

Art: The Past and Modern. Roli and Jansen, India. 2011.

Kunst, Scott. “Tulips With a

Past.” Horticulture Magazine. http://www.oldhousegardens.com/images/Tulips-With-A-Past.pdf February, 2002.

Levey, Michael. The World

of Ottoman Art. Charles Scribner’s Sons . New York, 1975.

Louvre. Three Empires of

Islam Collection “Iznik and Ottoman

Ceramics.”

Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Online Collections. http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/452854

Palace of Gold and Light:

Treasures from the Topkapi. Istanbul.

Palace Arts Foundation, 2000.

http://threadsofhistory.blogspot.com/2009/09/paisley-visual-history.html. Friday, September 18, 2009.

Porter, Venetia. Islamic Tiles. Interlink Books. Northampton, Massachusetts, 1995.

“Silks from Ottoman Turkey”. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tott/hd_tott.htm

“Silks from Ottoman Turkey”. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tott/hd_tott.htm

Sothebys. “Arts of the

Islamic World.” Online Catalogue. http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2008/arts-of-the-islamic-world-l08222/lot.265.html.

Turkish Cultural Foundation. “The Art of Turkish Textiles.”

Victoria and Albert Museum “Plant Motifs in Islamic Art” http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/p/plant-motifs-in-islamic-art/

.jpg)